the making and breaking of the portland vase

IN THE BEGINNING

“The best surviving example of what we refer to as the cameo technique. Do take a closer look, ladies and gentlemen. The detail is exquisite.”

The Vase has resided for the last 215 years in the British Museum in London. She was brought to Britain by William Hamilton in 1784, but before that had spent the whole of her life in Italy. We don’t know who commissioned her, but it would probably have taken about two years to make the Vase, and she would certainly have been very expensive. That being the case, the first Roman Emperor Augustus seems to be a good candidate for the position of original owner. This would mean that she was made a bit before or a bit after 1 BCE; and two other vases found in Italy created in the same ‘cameo’ style, though they are less elaborate, tend to confirm that date. This makes the Vase over 2000 years old. She is very rare. And she is made of glass

The Vase would have started life as a blob of silica (sand that contained alumina), mixed with soda ash (sodium carbonate) and lime. We think that the intense dark blue colour of her outer layer came from adding cobalt to liquid glass. The Roman writer Pliny the Elder tells us that glass was first discovered when some Phoenician sailors who had anchored their ship on the coast of Palestine set about cooking their dinner on the beach. They hunted around for a rock to put their cooking pot on, but when they couldn’t find one they used a lump of nitrum, naturally occurring sodium carbonate, from their ship’s cargo.

When the nitrum and sand melted in the heat from the cooking fire the sailors saw a stream of translucent material flowing down the beach. As it hardened it formed a lump of glass (Pliny the Elder, Natural Histories 36.66).

This account is chemically plausible. The nitrum and the sand provided the sodium carbonate and the silica. The lime (calcium oxide) may have been present in the sand as well, the product of ground-up sea-shells.

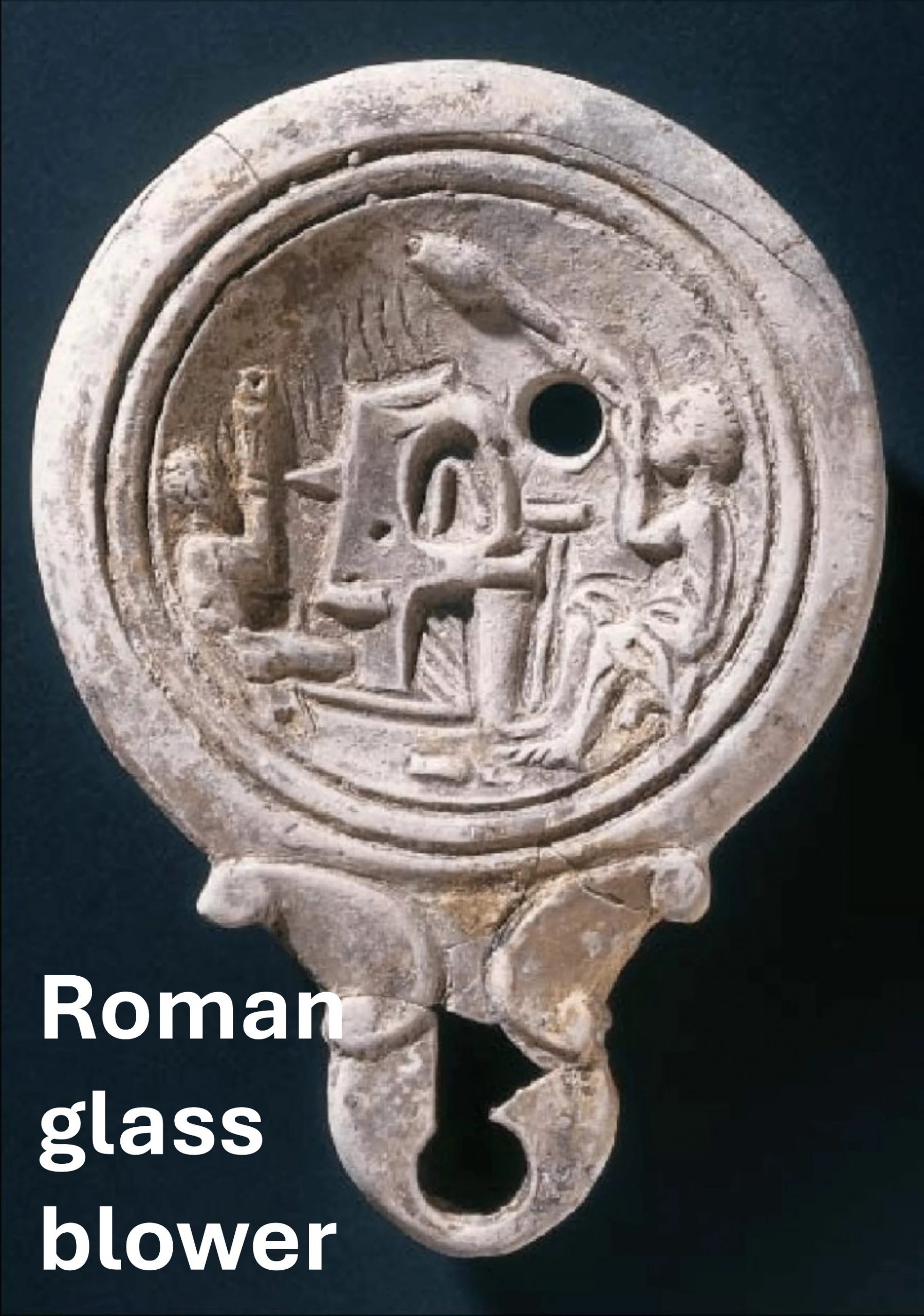

The Romans generally used a hollow steel tube or blowpipe to make glass vessels, gathering the molten material onto the end of the pipe and then blowing through it to inflate the glass into a bubble. We can see this happening on a terracotta Roman oil lamp which was found in Slovenia, one of the few objects to give us an idea of how glassblowing worked in about 70 CE.

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

‘No more! Please!’, the Vase groaned. ‘Somebody stop him! I’m going to burst!’

‘Marcus!’ said the Engraver. ‘That’s enough.’

‘Don’t be so edgy. I know what I’m doin’.’

The Glassblower clearly did know what he was doing. He gave one last huge blow, then stood back. ‘There. What do you think?’ He was pleased with his efforts, though he tried not to show it. Dio, he knew, was a perfectionist. It was hard to get a compliment out of him.

Many years later, in the Museum, the Vase said proudly to one of her companions, ‘Lord, it was hot in there. First my blue glass, then my layer of white. What a performance.’ It had indeed been a major performance.

Back in Rome, when the Vase was being blown, the Engraver Dio, who also found it very hot in the Glassblower’s workshop, mopped his brow. Marcus, still panting from all his exertions, was well aware that Dio was a man of few words as well as a perfectionist. But he thought that Dio looked impressed, in spite of himself.

‘It’s beautiful,’ said Dio.

‘Not bad, is she?’, said Marcus.

And the Vase at the time thought, Beautiful? Really? Do you mean it?

‘Think you can do it then?’ asked Marcus.

‘If I’m careful.’

‘Nearly three years it took him, carving my figures!’ the Vase said later to her friend in the Museum. ‘Can you imagine? Dear Dio, what an artist. Such tiny detail.’