For earlier blogs, go to

Mixed feelings

19 december 2025

His feelings remained complex: desire mingled with dread, affection with resentment, happy memories with bitter: it was one of his misfortunes that he seldom had a simple emotion: his pleasure was nearly always marred by nervousness, his happiness streaked with more disturbing hope.

Covid made us unhappy and labour hasn’t done much to change that. is that all there is?

4 october 2025

In 2023-24 happiness in the UK had still not returned to its pre-Covid levels. Fewer households believed their life was satisfactory (7.4 in 2023-24 compared to 7.45 in the previous year and 7.7 in 2019-20) and worthwhile (7.7 in 2023-24 vs 7.73 the year before and 7.9 in 2019-20), anxiety had risen (3.0 in 2023-24 vs 3.23 in the previous year, and 2.7 in 2019-20) and happiness had fallen (7.5 in 2023-24 vs 7.39 the year before and 7.6 in 2019-20).

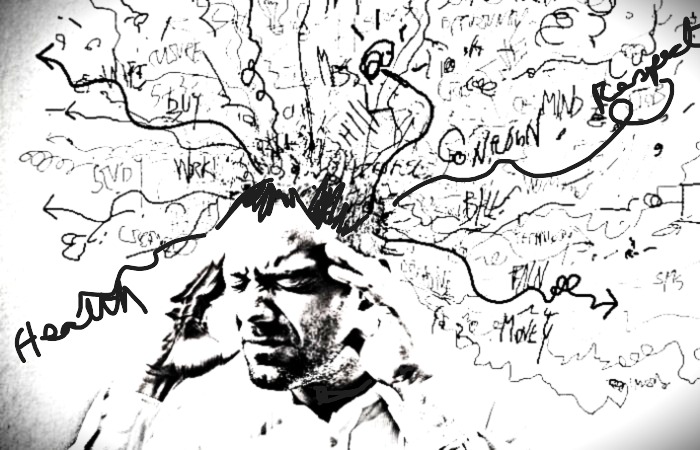

Are we anxiety addicts?

10 february 2025

Therapist Owen O’Kane believes the answer is ‘Yes’, and has just published a book about it. It’s called Addicted to Anxiety. How to Break the Habit (The Observer, Sunday 9 Feb). There’s no 12-step programme for anxiety addiction, O’Kane says. But it does resemble other, more mainstream addictions, in that it makes big promises which it can’t possibly keep.

‘I will protect you, I will keep you safe, I will stop bad things from happening.’ Who wouldn’t want that?

Anxiety is like a safety blanket, O’Kane argues, convincingly. It offers short-term relief from menacing thoughts, but as a coping mechanism it can be self-sabotaging. ‘I can guarantee that nothing will go wrong if you avoid that dinner-party. I can promise you that you won’t feel rejected if you don’t apply for that job….’ The problem is, the more hooked you become, the bigger the anxiety becomes, and you get caught in this almost circular loop. So we get addicted to anxiety because, paradoxically, it gives us a way of dealing with our fears. We just give in to them. The next time we’re scared, we’ll say to ourselves, ‘No, dinner-parties like that make me so anxious. But that’s OK, they just aren’t for me. I don’t have to go.’

The solution, of course, is a tough one. You have to say ‘No’ to fear. Accept it exists, but negotiate with it – say, ‘Thanks, but I don’t think on this occasion that staying in bed will be the long-term solution.’ Then gradually fear will lose its power over you.

It’s hard, but I’m sure O’Kane is right. My poor late mother was a case in point. By the time she was in her 80s she was so anxious about everything that she just sat at home, all the time – for about eight years.

I resemble her in many ways. But for some time I’ve been so determined not to end up in her state of mind that I’ve developed the obverse problem. My Mum’s negative role model has instilled in me a philosophy that insists, if something scares me, I’ve got to do it. So for me, the trick is to sort out which of the scary things I really ought to be attempting, and which I can safely leave alone. Confronting EVERY terror is probably too much. Years ago, when some of our neighbours were doing a parachute jump to raise funds for our local advice centre, I almost convinced myself that I was duty-bound to take part. I’m still glad that I didn’t.

more on the dark times

21 january 2025

Yesterday evening a well-timed concert at the Wigmore Hall in London asked a question first posed by playwright Berthold Brecht in a motto attached to his Svenborg Poems: ‘In the dark times will there also be singing?’ He answered the question himself, in the affirmative: ‘Yes,’ he wrote, ‘there will be singing, About the dark times.’ The Poems were published in 1939. His close friend, the German philosopher Walter Benjamin, agreed. In the following year, in On the Concept of History, Benjamin warned us that, ‘the “state of emergency” in which we live is not the exception but the rule. We must attain to a concept of history that accords with this insight.’

All this seemed very appropriate on the day when Donald Trump was inaugurated as US President. It was also ‘Blue Monday’, said to be the most depressing day of the year.

But the concert, which featured the glorious voice of contralto Jess Dandy, with Dylan Perez on piano, presented some dissenting views of darkness. Not just a metaphor for times of tribulation, nor a necessary prelude to seasonal renewal, but also a recurring and diurnal reality which can shelter and sustain: something more akin to Heidegger’s conception of Earth, and ‘a fertile darkness of infinite potential.’ (Jess Dandy and Dylan Perez, Programme Note, In the Dark Times will there be Singing?) The evening ended with some settings of poems from Rainer Maria Rilke’s The Book of Hours, composed by Alex Mills and translated by Anita Barrows and Joanna Macy.

You darkness, of whom I am born –

I love you more than flame

that limits the world to the circle it illumines

and excludes all the rest.

But the dark embraces everything:

shapes and shadows,

creatures and me

peoples, nations – just as they are.

It lets me imagine

a great presence stirring

beside me.

I believe in the night.

Rainer Maria Rilke, Book of Hours

happy new year? embrace the darkness

17 january 2025

Last week on BBC Radio 4 Adam Gopnik struck a chord when he pointed out that many people in the Northern hemisphere find January harder to deal with psychologically than November or December, even though the sun has been reborn and the days are getting longer. This, he suggested, is because many religions have festivals which help us to get through the earlier dark months – Hanukkah, Christmas, Diwali, the Winter Solstice, and so on. But in January these are all over. We’ve only got Spring to look forward to, and that seems a long way off.

But what’s so bad about darkness, especially now that we have electricity to help us? Perhaps, said Gopnik, it’s time for us to come to terms with the temporary absence of light. It has many positives. For example, moths generally prefer the dark, and light pollution is resulting in a serious decline in their numbers.

It’s true that in the history of human thought light has been linked to rationality. Witness in Britain the Enlightenment, in France – even more baldly – Les Lumieres, or in Italy L’Illuminismo. This, I think, is misguided.

A number of philosophers have questioned the value of bringing everything to light. The twentieth century German thinker Martin Heidegger, for example, argued that ‘Earth’ is an inherently dynamic dimension that simultaneously offers itself to and resists being fully brought into the light of our ‘Worlds’ of meaning. Our efforts to expose the Earth’s ‘inexhaustible abundance of simple modes and shapes’ fuels what Heidegger calls the ‘essential strife’ between ‘Earth’ and ‘World’.

The World, in resting upon the Earth, strives to raise the Earth completely [into the light]. As self-opening, the World cannot endure anything closed. The Earth, however, as sheltering and concealing, tends always to draw the World into itself and keep it there

Heidegger’s view is that if a work of art is to preserve a meaningful ‘World’ for its reader, audience or viewer, it must maintain the essential tension between the World of meanings and the more mysterious phenomenon of Earth. In this analysis, Earth both informs and sustains this meaningful World and also resists being interpretively exhausted by it. The fluctuation between light and darkness must be maintained if meaning is to be both created and questioned.

So let’s embrace the dark, and allow it to nurture our thoughts and schemes, before they’re subjected to the harsh light of day.

don’t sell off the orchard for an apple

19th June 2024

‘What pride can there be, … if in the vast majority of cases (a man) is coarse and stupid and deeply unhappy? We must stop admiring one another. We must work, nothing more.’

Twelve years ago I noticed so many references to happiness in a Benedict Andrews’ production of Chekhov’s Three Sisters at the Young Vic that I was inspired to write a blog about it . So earlier this month I was delighted by the unexpected ‘déjà vu’ of Andrews’ brilliant The Cherry Orchard at the Donmar Theatre. Similar theories – now or not now, love or work – are aired and debated, in particular by the eternal student and talker, Trofimov. (See https://sueblundellhappiness.wordpress.com/2013/04/ ).

Trofimov basically believes that happiness is unachievable in his own day and age. But if we work hard we may make happiness a possibility for those who come after us.

‘The human race progresses, perfecting its powers. Everything that is unattainable now will some day be near at hand and comprehensible, but we must work, we must help with all our strength those who seek to know what fate will bring.’

And our fate – which for Trofimov seems to be tied up with human progress – determines that one day people will be happy.

‘Forward! We go irresistibly on to that bright star which burns there, in the distance! Don’t lag behind, friends!’

But oh how much he wants it to be now.

‘Yes, the moon has risen. [Pause] There is happiness, look, there it comes; it comes nearer and nearer; I hear its steps already. And if we do not see it we shall not know it, but what does that matter? Others will see

it!’